The Proof Is in the Pudding

I’ve always hated that expression. What does that even mean? The proof of what is in my pudding? The original expression was more along the lines of “the proof of the pudding is in the tasting/eating”. Idiomatically, we all understand the abbreviated version to mean, “I’ll believe it when I see it” or in general, that the value, effectiveness and even existence of something cannot be validated until it is tested.

Show Me the Code

In software engineering we have a similar, albeit less abstract, expression: “show me the code”. I’m sure there are similar expressions in other professions. I know there was an expression in the movie Goodfellas that was similar in its unapologetic tone (I’ll leave identifying this expression as an exercise for the reader – it’s a great movie anyway). In the software world, however, what we’re trying to express is that an idea, diagram, proof-of-concept, and basically anything that is not actual production code is, well, “worthless”.

Okay, I was being hyperbolic with “worthless”. There is a ton of value in all the things that I mentioned, but that value doesn’t materialize into business value until those things are expressed as functioning production code.

Talk is cheap. Show me the code.

Linus Torvalds

Do you have a brilliant idea? Great; show me the code. Do you have an academic paper extolling the virtues of some process? Great; show me the code. Have you put together an architectural diagram? Great; show me the code.

The 90/90 Rule

The 90/90 rule, is a humorous observation attributed to Tom Cargill of Bell Labs in the 1980s:

The first 90 percent of the code accounts for the first 90 percent of the development time. The remaining 10 percent of the code accounts for the other 90 percent of the development time.

Tom Cargill, Bell Labs

What I’ve seen time and time again is the most talented engineers are hyper-engaged and focused early in a project, for the “fun stuff”. This might include playing with a new language, library, or platform. It might mean spinning up cloud resources and building out a cluster. It may mean tearing open some hardware and reverse-engineering it. It may mean working some magic to performance tune some questionable part of the system. In short, it’s stuff that’s new and novel.

You see, engineers get bored easily. We don’t want to spend time doing the same thing over and over; we need shiny new toys to excite the neurons in our brains. Because of this, our excitement tends to wane as projects progress. What was new and exciting becomes boring and stale.

Once the novelty wears off, engineers get an itch to move on to the next shiny new toy. They don’t want to be tied to some project that’s entering the dreaded “maintenance mode”. They don’t want to be answering user questions or writing documentation or convincing management that component XYZ needs to be refactored, so development starts to slow as engineers divert their energy to more exciting projects.

Show Me The (Finished) Code

With software, nothing is ever truly done, we just asymptotically approach zero features and defects. But there is a version of done where we’ve met our business requirements and provided peak business value. This is just before we reach the zone of diminishing returns.

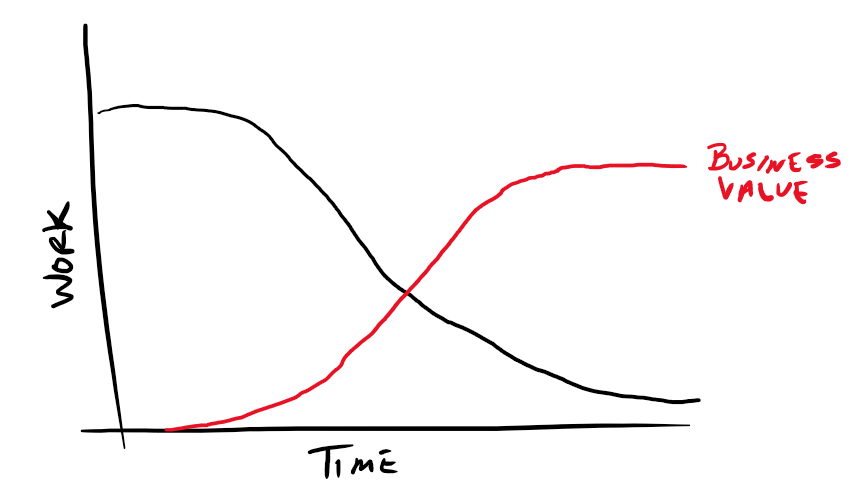

This is probably best illustrated by the expertly drawn diagram above (Fig 1). As the amount of “work” to be done (features to be implemented/outstanding defects) decreases, business value (ideally) increases. Eventually, over time, we stop producing additional business value and enter a phase of diminishing returns. This is oversimplified, but what it is meant to illustrate is that we produce the most business value toward the end when most features are implemented and most defects are resolved.

So, our expression, “show me the code” is imprecise. Not only do you need to “show me the code” as it is now, you need to show me the plan for how to get to “done”, your plan to get it into production, and your commitment to producing peak business value. I’m not suggesting that we adopt a new expression with this level of verbosity, we just need to collectively make sure that we agree at what “show me the code” is trying to elicit.

Toward Building Value

Our jobs as engineers is to provide value to the businesses that employ us. We are biological machines that are tuned to take complex, abstract, problems and turn them into delivered products and services. The key word being “delivered”.

While there is value in ideas, proofs-of-concept, research, and experimentation, the “proof of the pudding” is in deploying your software to production and then diligently supporting that software until such a time that your time is better spent elsewhere.

So true in so many industries!